Combining a Calling and a Passion: Using Art in the Operating Room

March 24, 2022

By: Riverview Health

Categories: Plastic Surgery, Riverviews

Tags: Botox, Brazilian butt lift, Breast augmentation, breast reconstruction, breast reduction, cancer reconstruction, cosmetic surgery, Fillers, lipsuction, plastic surgery, trauma plastic surgery, tummy tuck

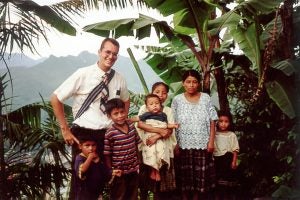

Joshua Tieman, MD, always knew he wanted to pursue higher education. A talented student with an eye for art, he was drawn to medicine but wasn’t sure which direction life would take him. However, while serving on a two-year religious mission in Guatemala, the decision to pursue medicine was solidified for him.

In the high mountain villages of Guatemala with no running water or electricity, healthcare consisted of small community clinics, usually with a single doctor.

“Seeing an entire village line up in front of these small clinics to see one doctor had a profound effect on me,” Dr. Tieman said.

Many of the injuries and health problems Dr. Tieman encountered among the community were problems that could be easily addressed in the United States. Yet, due to a lack of resources and specialized physicians, straightforward injuries would turn into lifelong impairments in Guatemala. Filled with rich, dense jungles, the implications of everyday accidents and basic wounds could greatly alter the livelihood of villagers and their families.

“Everyone in Guatemala carried machetes, and there were injuries all the time. From small cuts to big wounds, a surgeon was needed to treat these injuries. But there were no surgeons for miles, so members of the community left these ailments untreated or were placed in the position to treat it themselves,” Dr. Tieman said. “This resulted in people left with infections, missing fingers, toes and even hands. It was powerful to see what a lack of medical care could mean for people. That was the deciding factor for me to become a surgeon.”

In his downtime, Dr. Tieman had always enjoyed expressing his creative side, but during medical school, creating art began to feel more like a chore than a hobby. He drew medical illustrations to study for his exams, turning a once creative outlet into a study tool. His talent was soon recognized by colleagues, and Dr. Tieman’s work was used in multiple published medical journals. But despite the praise, Dr. Tieman began to lose the joy he once felt in the artistic process.

four Mayan languages.

“I felt like I lost myself. I never wanted the work component of my art to make me not enjoy the process,” Dr. Tieman said.

In between his first and second year of medical school, Dr. Tieman received a National Institutes of Health grant to research breast cancer reconstruction at the University of Utah. It was during this time when he got his first in-depth look into what plastic surgery really entailed. From that point on, he knew it was the specialty for him. Not only did it fulfill his desire to perform surgery, but he also found joy in the artistic process again when he was able to sculpt what his patients envisioned and ultimately boost their confidence.

Dr. Tieman began his fellowship in plastic surgery at the University of Utah and described his training as “busier than I had anticipated.” However, it was during that time when he felt the urge to draw again as he spent months perfecting a portrait of a late family member.

“I redeveloped and regrew when studying plastic surgery. We learned about prioritizing aesthetics, and that was something I used in my art,” Dr. Tieman said. “By using what I know about art, drawing and aesthetics, I really have my own personal style that I get to show off in plastics.”

Dr. Tieman’s passion is displayed through his process while preparing for a cosmetic surgery.

“I operate on a patient two to three times in my head before I get into the operating room,” Dr. Tieman said. “We take preoperative photos of the patient, I go home and think—deciding how I want to go about the surgery. I picture it in my head, I write it out, I draw it.”

Aside from using his artistic abilities, Dr. Tieman loves plastic surgery because of the relationship and trust he builds with patients.

“The real beauty of this field is our ability to help patients see themselves in a new light,” Dr. Tieman said. “By learning their story and seeing how one procedure can give them this newfound confidence, you realize just how impactful your work can be.”